On Monday, the United States Holocaust Museum joined those opposed to Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s characterization of the conditions and facilities housing migrants, stating how it “unequivocally rejects efforts to create analogies between the Holocaust and other events, whether historical or contemporary.”

It stood well apart from what historians and descendants of the Holocaust have been saying, prompting one prominent lawyer to suggest “the practical application of ‘Never Again’ apparently is to make the Holocaust definitionally sui generis, ruling out any comparison of its precursors to contemporary conditions no matter how similar and appalling.”

It’s undeniable that the U.S. government is warehousing children in conditions so appalling, former Department of Defense special counsel Ryan Goodman says they are “worse than the most basic standards required by international humanitarian law for enemy prisoners of war.”

Tuesday saw the sudden resignation of John Sanders, acting commissioner for the Customs and Border Protection agency, with the situation growing increasingly chaotic.

While attention has rightly shifted to substantive matters of policy, one particularly insightful column regarding the debate on terminology is worth highlighting:

But the argument is really about how we perceive history, ourselves, and ourselves in history. We learn to think of history as something that has already happened, to other people. Our own moment, filled as it is with minutiae destined to be forgotten, always looks smaller in comparison. As for history, the greater the event, the more mythologized it becomes. Despite our best intentions, the myth becomes a caricature of sorts. Hitler, or Stalin, comes to look like a two-dimensional villain—someone whom contemporaries could not have seen as a human being. The Holocaust, or the Gulag, are such monstrous events that the very idea of rendering them in any sort of gray scale seems monstrous, too. This has the effect of making them, essentially, unimaginable. In crafting the story of something that should never have been allowed to happen, we forge the story of something that couldn’t possibly have happened. Or, to use a phrase only slightly out of context, something that can’t happen here.

The thread previewed below, written last summer when news of family separation and mass detention first garnered attention, is worth revisiting.

It pairs well with the viral clip of a Trump official arguing the merits of the inhumane treatment of migrants, which many felt exemplified “the banality of evil in modern times.”

“The truth is more complex, but still appalling,” former federal prosecutor Ken White writes in The Atlantic. “The sheer effrontery of the government’s argument may be explained, but not excused, by its long backstory.”

That backstory is worth reading in full, but the following points are key:

It is right and fit to condemn the Trump administration for its argument and its treatment of children. But it’s wrong to think the problem can be cured with a presidential election. Trump will depart; the problem will not depart with him. This administration is merely the latest one to subject immigrant children to abusive conditions.

The fault lies not with any one administration or politician, but with the culture: the ICE and CBP culture that encourages the abuse, the culture of the legal apologists who defend it, and our culture—a largely indifferent America that hasn’t done a damn thing about it. This stain on America’s soul will not wash out with an election cycle. It will only change when Americans demand that the government treat the least of us as both the law and our values require—and firmly maintain that demand no matter how we feel about the party in power.

Time and again, justification for unjustifiable atrocities against some “other” is the end point of gradual, escalating dehumanization, which is the crux of what AOC initially argued.

A privileged discussion

Back in May, CNN’s Andrew Kaczynski and team explored Joe Biden’s personal relationship with Mississippi Democrat John Stennis, a “respected member of the senate but longtime opponent of civil rights and desegregation who Biden called a ‘hero of time.’”

“Now in his third run for the presidency, Biden presents his ability to respect and work with ideological opponents as an asset that could return the country to a bygone era of bipartisanship and consensus,” they wrote.

That story, paired with one similar which followed, served to demonstrate that however noble his intentions, Biden doesn’t seem to understand the unworkable nature of his approach in the modern political sphere, or the strong reaction to his words.

“If a white segregationist doesn’t call you ‘boy’ it’s because you’re white. That’s it … he didn’t see you as part of ‘an inferior race’,” Smith concluded.

An aside: This controversy provided a few great opportunities to learn, thanks in part to those who are stubbornly and perpetually immune to facts.

While condemnation of Biden’s remarks and subsequent defensiveness wasn’t unanimous—civil rights icon John Lewis offered an unequivocal defence of his colleague—it wasn’t driven by “white woke progressives” as alleged by the right’s dedicated culture warriors any more than the backlash to Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s justification for opposing reparations was.

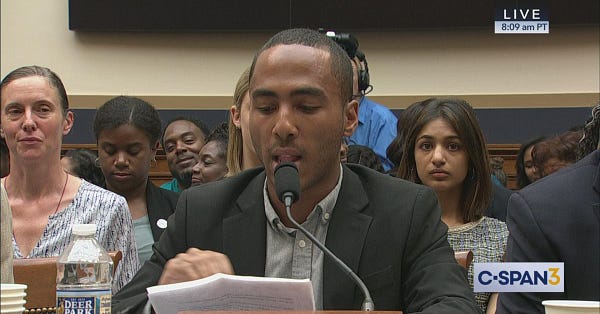

In the latter case, the most powerful rebuke came from widely-respected writer Ta-Nehisi Coates, who testified before the House Judiciary Committee as it explored the case for reparations.

We grant that Mr. McConnell was not alive for Appomattox. But he was alive for the electrocution of George Stinney. He was alive for the blinding of Isaac Woodard. He was alive to witness kleptocracy in his native Alabama and a regime premised on electoral theft. Majority Leader McConnell cited civil rights legislation yesterday, as well he should, because he was alive to witness the harassment, jailing, and betrayal of those responsible for that legislation by a government sworn to protect them.

What they know, what this committee must know, is that while emancipation deadbolted the door against the bandits of America, Jim Crow wedged the windows wide open.

It’s far too easy for the white population to forget or dismiss just how recent the subjugation and state-sanctioned discrimination against the black population was.

This isn’t ancient history.

Take, for instance, Lester Townsend who, in 2016 at the glorious age of 108, met with then-president Barack Obama.

“The grandson of a slave shaking hands with the president of the United States,” Townsend marvelled. “I never thought I’d live to see this.”

Townsend’s larger story, as detailed in Essence, really underscores the meaning of that moment.

“My grandfather, he and his brother were given to his old master for his daughter’s wedding present. They were young men but they were given to him. I tell you, to think how far we have been behind and come this far, we’re not there yet, but we’re on our way.”

Just last year, Richard Overton—at the time, America’s oldest WWII veteran—died at the age of 112. A thread paying tribute to his remarkable life noted this “grandson of a slave, served in a segregated unit, the 1887th Engineer Aviation Battalion, in Pearl Harbor after the attack.”

Still, the very idea of reparations—not even set policy, simply the notion—continues to prompt asinine commentary from a large swath of the right.

One voice in the anti-reparation chorus is worth closer examination. Compare the most-cited quote from Coleman Hughes, captured below, to that of O’Reilly above. The logic remains absurd, but coming from a black man, such a mindset becomes more acceptable for a white one to openly share.

There were some telling reactions to those who simply mentioned the name of the publication which hosts and champions Hughes, one which routinely claims to be above or beyond tribalism.

And as has become typical, Quillette editors chose to amplify only the most obscene tweets regarding Hughes’ testimony before the subcommittee, rather than elevate any number of thoughtful responses offered.

Below, for instance, touches on survivorship bias:

And here, an entirely fair characterization of why Hughes has captivated a certain audience (with images to illustrate in the full thread): “He said he actively didn't try hard in high school because he knew being black would give him an advantage to get into college … he suggests there's social capital to be gained by identifying as black.”

In my view, this doesn’t suggest individuals operating in good faith.

In the end, this conversation reminds me of an interview from 1967 I recently came across, where Martin Luther King Jr. eloquently explains—without using the words—the concept of “white privilege.”

That term, understandably, is one which many reflexively bristle at. The aggressive nature of some activists in the social justice community has made it almost impossible to have any meaningful conversation following the invocation of those two words. This short clip, however, offers a clear, powerful articulation of the reality.

What’s your type?

A Venn diagram of those who believe Juanita Broaddrick but who doubt everyone else…

Some are asking legitimate questions, and having necessary conversations.

Others are telling on themselves.

If you’re going to run a piece calling into question the credibility of a woman who comes forward with a story of sexual assault, especially where contemporaneous accounts of the misconduct exist, perhaps seek out individuals who aren’t entrenched in the violently misogynistic extreme of Men’s Rights Activism, or who aren’t on the record defending convicted pedophiles against what they baselessly claim are “false allegations,” or who haven’t dedicated their lives to undermining the credibility of sexual assault survivors.

Or, at least, who hadn’t already made up their minds.

One more thing…

When They See Us, a docudrama on Netflix which explores The Central Park Five has earned as much praise as Chernobyl from those in my circle. I’ve yet to see it, but I’m told it is well worth the time and I plan on giving it a try this weekend. Because I don’t have anything unique to recommend for this week’s newsletter, I thought I’d pass along this suggestion.

As described by Emily Nussbaum, When They See Us is “a harrowing story about a hideous injustice: the railroading of a group of five black and Latino boys for the beating and rape of Trisha Meili, who was attacked while jogging in Central Park, in 1989. The show portrays a racist justice system and an equally hellish penal system, as well as media that amplified the lies that put the boys in prison. But its main concern—its method and its theme—is empathy. Not a syrupy, manipulative empathy but a rigorous one, meant as a corrective. As the title indicates, it takes boys who were seen as a group—reduced to an indistinguishable pack of animals—and insists that they be viewed as individuals, children worthy of love, and then, years later, men worthy of justice.”

If you enjoyed this week’s newsletter and think you know someone else who would, feel free to pass it along. Stay tuned for more ms.info on Wednesday afternoons.

New subscribers can sign up by clicking below: